Throughout our life we grow by giving up.

I read this line on The Marginalian this morning and wrote it down. It’s pulled out of Judith Viorst’s book, Necessary Losses.

It grabbed my attention because it seems wrong. Her wording renders it off-putting, for “giving up” has such a negative connotation. We are told to never give up. That giving up is weak, and holding on is strong. But that’s not always true. I think of Atul Gawande’s book, Being Mortal, and how brilliantly he discusses death and our futile opposition to it. As a surgeon, he explains that there is just as much, if not more, strength in knowing when to give up, as there is in fighting to hold on. Toddlers know how to hold on. Little kids know how to put up a fight. But neither have yet learned how to lose. How to give up with grace. How to let go.

I think also, as The Marginalian did, of Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “One Art”. It opens with, the art of losing isn’t hard to master. I can still hear my college professor’s voice reading it out loud to us melodiously. I stared at the palm fronds tapping against the windows, feeling the California breeze kiss my shoulders as poetry landed in my ears, the lines pirouetting into my mind like ballerinas. I adored the wording, for losing was not an ugly, shameful thing, but an art. I would though.

IN LOVE WITH YOUR LOSSES

Writers are all secretly in love with their losses.

They offer the most fertile soil with which we can cultivate our own little gardens of revelation. Loss teaches us everything. It shatters our world and dares us to build it back up again, to pick the glass out of our knees and stand up again. And even long after we do, the loss stays. It writes itself into our DNA, becoming an inextricable part of how we experience the world. It either makes it a terrifying place, or one that is all the more beautiful.

When I think of loss, I tend to think of coming of age. Which is ironic, for those years are really filled with so much gain. My first thought when I read anything like Viorst’s book, is of heartbreak. Heartbreak as it came in the expected package of failed relationships. I automatically think of the day, the event, the time that I first met loss. I think, there was before, and then there was after.

Which is true enough.

But Viorst makes a point of loss being so much deeper than that. While she is a bit too freaky Freudian for my taste, she makes the point that we meet loss on the day that we are born. From that first, screaming breath, we are filled with the ache of being yanked from the womb and brought out into a world that is far too cold and loud and bright. We become a being that is separate from our mother. Which, she explains, is to become a being that is vulnerable to the human experience in all of it’s multifaceted glory. An experience that no one can weather for us.

We begin life.

Joan Didion’s words comes to mind—Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss. Children afflicted at birth with some presentiment of loss. Children who cry when the ball is placed behind your back because object permanence has yet to be learned, but loss hasn’t. I think of my own childhood and realize that I did not, in fact, meet loss for the first time when I came of age. I had been meeting it all my life in the ways that every human does. Slowly I remember sitting under trees with my journal as a kid, writing about childhood ending. Writing about how it felt to feel imaginary worlds dissolving from my reach, toys and dolls no longer animated. No longer alive.

ALL AROUND

Viorst was right.

“When we think of loss we think of the loss, through death, of people we love. But loss is a far more encompassing theme in our life. For we lose not only through death, but also by leaving and being left, by changing and letting go and moving on. And our losses include not only our separations and departures from those we love, but our conscious and unconscious losses of romantic dreams, impossible expectations, illusions of freedom and power, illusions of safety — and the loss of our own younger self, the self that thought it always would be unwrinkled and invulnerable and immortal.”

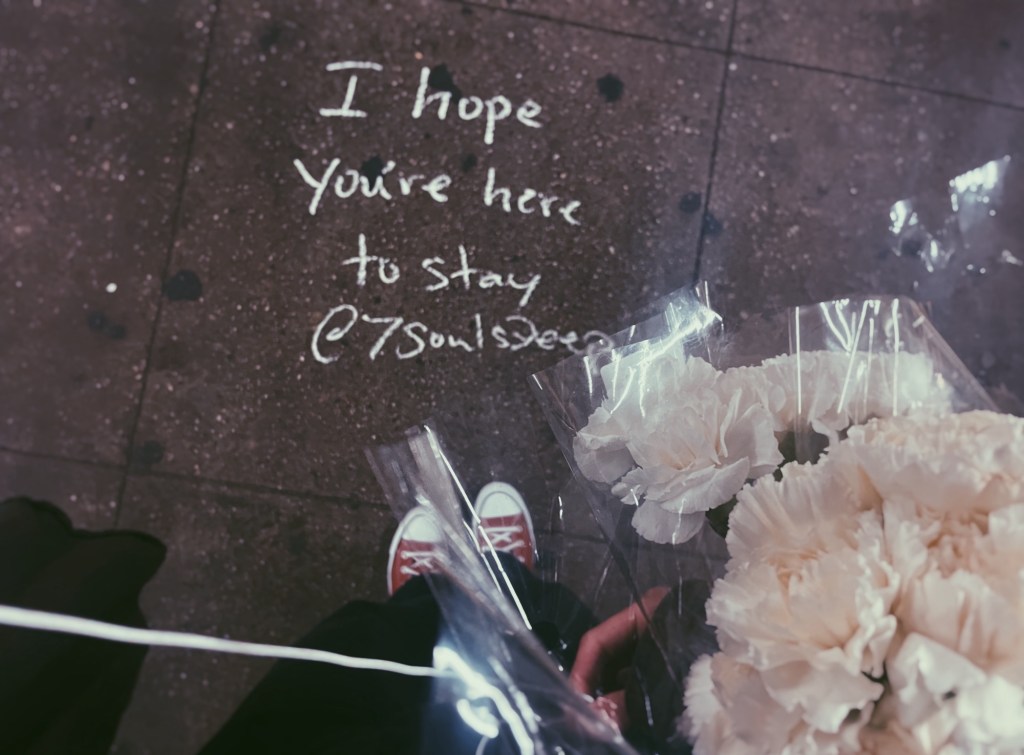

Loss is far more encompassing than a break up or a death. We inhale it’s molecules from the day that we are born and it stick inside our lungs, reminding us with every breath that we are deeply ephemeral, vulnerable bundles of biology. I realize now that coming of age was not when I met loss, as much as it was when I learned how to lose. It wasn’t that it was the first time I felt heartbreak as much as it was the first time I actively healed from and found beauty within it.

It was the very beginning of my coming to terms with the fact that growing up is learning when to give up, and what of. It’s finding freedom and peace within the relinquishment of the ropes that we anxiously let burn our hands as children who had no interest in letting anything go, ever.

It’s realizing that letting go is a form of art, not an acquiescence of strength.

Click here to support a small artist with big dreams (me)

ABOUT SPINNING VISIONS

A space dedicated to documenting experience and exploring thought. Click here to read more.

GET ON THE LIST

Give your inbox something to look forward to.

Leave a reply to Makenna Karas Cancel reply